Lab to launch: marketing milestones in drug development

Progressing the discovery of a life-changing medicine is complex, risk-ridden and expensive. It’s also heavily reliant on effective healthcare communications for its success…

This article will:

- Explain the drug discovery and development process

- Set out the audiences and external/internal stakeholders involved

- List communications and milestones through to launch

- Reference the compliance responsibilities

enshrined by the ABPI code

Sarah Monaghan is a copywriter who specialises in the life sciences, pharmaceutical and healthcare fields and a member of the Healthcare Communications Association and Medical Journalists' Association

Contact her at sarah@connectedcopy.co.uk

The insight in this article is drawn from various sources and experiences but I'd like to thank the Healthcare Communications Association for its excellent 'Molecule to Marketing' course which gave me valuable perspectives on the topic.

It all begins at the bench

Right now, thousands of different scientific research teams, spanning academia, major pharmaceuticals, biotechs and contract research organisations (CROs) are delving into diseases to try and decipher their origins.

Their decision to focus on a specific therapeutic area will be driven by factors like unmet need, prevalence and urgency (as with COVID-19). Considerations like research expenditure, market rivalry and prospective market share will also weigh in.

R&D: Balancing Pragmatism and Innovation

Often, when it comes to R&D in the drug discovery process, the yin-yang of the industry pulls it in opposite directions.

● The yin side is drawn towards short-term and goal-oriented R&D within ‘strategically’ or ‘clinically’ important therapeutic areas (such as chronic conditions like Alzheimer’s or diabetes, with a higher likelihood of reliable returns due to significant unmet medical needs or large patient populations).

● The yang side is drawn towards blue skies (and inherently riskier) R&D in the hope of discovering pioneering molecules or novel modes of action. CAR-T, a type of immunotherapy that uses genetically modified T cells to treat certain cancers, was an example of this kind of pioneering, high-risk, high-reward R&D.

When a disease's biological target, such as a receptor, enzyme, protein or gene, is identified, the hunt begins in the hope of finding the chemicals or natural compounds that might inhibit or enhance its activity, with the goal of combatting – or even – reversing the disease progression.

To get there, tens of thousands of molecules and compounds will be reviewed, sourced from both naturally occurring and lab-synthesised compounds. The financial outlay to develop this New Molecular Entity (NME, if it’s a small molecule compound) or New Biological Entity (NBE, if it’s an antibody, protein, gene therapy, or other biological medicine) will likely run to over $1billion. Yet the probability of it resulting in an approved new medicine is incredibly slim.

A 90–95% chance of losing your entire investment in a drug isn’t a risk shared in any other industry. But the hard truth is that only one out of those thousands of molecules and compounds will make it through the research and clinical process. And even fewer will become transformational and profitable medicines that improve people’s lives.

A marathon, not a sprint

This work is, though, now being speeded up with Artificial Intelligence. AI’s number-crunching algorithms are transforming discovery research by filtering datasets for relevant compounds, advanced lead modification and generating drug candidates.

Sometimes it’s a case of reigniting old data…

Innovative ideas aren’t always about generating something ‘new’. Dead ends can become detours, for example, with the use of molecules that may have ‘failed’ in one use case but that have another potential therapeutic application.

● The speed of the development of the COVID-19 vaccines illustrates this point. The mRNA technology behind the vaccines was created initially to interrogate basic molecular processes for the treatment of cancer – and only later found to be applicable to SARS-CoV-2.

● Recently, too, thalidomide (marketed in the late 1950s to alleviate morning sickness during pregnancy but then banned in 1961 as it caused severe birth defects) has been repurposed. It is now used for treatment of multiple myeloma (MM), becoming the first effective new drug to treat MM in decades and has given rise to a next generation of immune modulators.

The Race to Market

When a new drug candidate is finally identified (following pre-clinical non-human studies), the research team will apply for clinical testing approval from the relevant regulatory agencies. These are the FDA in the US, EMEA in Europe, and MHRA in the UK.

For the researchers, hereon, there will be another burning priority: speed to market.

The race against the clock is now on because any patent, once achieved, will tick down for a given amount of time only to cover the return on investment – and, ideally, more profits, for continued drug discovery.

When a drug is patented, it grants the holder an exclusive right to produce and sell the drug, typically for a period of 20 years from the date of filing. So every moment counts. Once the patent expires, other companies become free to produce generic versions which can substantially reduce the original drug's market share and profitability.

Humira, for example, is a blockbuster anti-inflammatory drug made by AbbVie, earning it nearly $200 billion from sales. It is losing its market exclusivity in 2023, paving the way for 'copycat drugs'. Similarly, Pfizer's Lipitor (atorvastatin), once the best-selling cholesterol-lowering drug in the world, lost its patent in 2011, since when multiple generic versions have entered the market.

According to the FDA, it takes, on average, 12 years for an experimental drug to progress from bench to market. So, when you know that US patents on new drugs only last 20 years, you can relate to the sense of urgency: half of the patent time could be spent in the research and regulatory approval phases.

FIH (First in Humans); POC (Proof of Concept)

Clinical Trials to Approval

If approved, the drug now begins to proceed through three clinical trial phases, with checks and balances every step of the way and a progressively intense focus on safety and efficacy. This moment marks the first instance of the new drug being administered to human subjects, with safety being a paramount concern.

Not many of the drug candidates, however, will make it all the way through the process below.

The Drug Testing PATHWAY: Phase I to III

Phase I trials: these normally involve about 20 to 80 healthy volunteers to establish a drug's safety and profile, and take about one year.

Phase II trials: these will involve approximately 100 to 300 patient participants to evaluate the drug's efficacy for a particular disease or condition. This stage spans roughly two years. Cohorts of comparable patients might be given the actual medication, a placebo (a non-active pill), or another effective drug to gauge the drug's impact. The safety profile and potential adverse effects are also examined.

Phase III trials: these tend to be larger, ensuring the drug's safety and efficacy across a wider demographic. They’re known as ‘pivotal studies’ because they aim to provide the critical evidence to support regulatory submission. These studies usually involve several hundred to 3,000 patients who are observed in clinical settings and hospitals to meticulously gauge efficacy and detect any additional adverse reactions. For rare diseases, the number of study participants might be smaller. A diverse group of patients, spanning various types and age brackets, are assessed. The researchers might also explore varying dosages and consider the experimental medication in conjunction with other therapies. On average, this phase lasts around three years.

If the trials are successful, the research team is now finally ready to submit a New Drug Application (NDA) to the regulator.

This application will be packed with pages of data and evidence rivalling War and Peace in length. It will undergo the thorough scrutiny of the keen eyes of scientific and regulatory experts to check that the drug is effective, safe, and meets manufacturing quality standards.

Only those drugs deemed safe and effective will be endorsed for market entry to be made available to healthcare professionals and the public. If the regulators are satisfied, a marketing authorisation or licence is issued. This allows the product to be sold by the licence holder in the regions covered by the regulatory authority. Price negotiations begin with potential buyers (government agencies or insurance companies, depending on the healthcare system – in the UK, it is the NHS, with guidance from NICE (National Institute of Health and Care Excellence).

The Moment of Launch

For communications teams working within the pharma company, this moment of launch is the critical comms opportunity. The successful launch of a new drug on the market will be the result of a detailed plan and a solid narrative. The team will have already communicated pre-launch news, trial results, regulatory landmarks and cultivated relationships with stakeholders and advocates over the pre-launch phase.

Now they’ll be looking for maximum reach with key players such as the media, external specialists, healthcare professionals, government bodies and patients. This is likely to involve multiple teams including sales, communications, PR, medical, corporate, and government affairs, with coordination across global, regional, and local levels.

This work won't stop at launch either. The subsequent years they'll be signposting further achievements, underlining the efficacy and advantages of the new drug and monitoring awareness and opinions.

Post-Approval and Beyond

Likewise, the clinical evaluation of the drug doesn't end at launch. Post-marketing Phase IV interventional studies or non-interventional research will take place to ensure the drug can keep its promises in real-world scenarios too.

Additional data about the product's safety, efficacy, or optimal use will be gathered – all information that’s essential to decision-makers for reimbursement and access.

A Remarkable Journey

The outcome of this extensive process has been the result of allowing scientists to follow their ideas and to take a risk.

It might be just a tiny white pill taken with water twice daily. But bringing this one drug to life will likely have involved up to a thousand individuals, spanned 12 to 15 years, and incurred research costs ranging up to $2.6 billion.

In short, how that single pill came to be in our medicine cabinets is anything but simple.

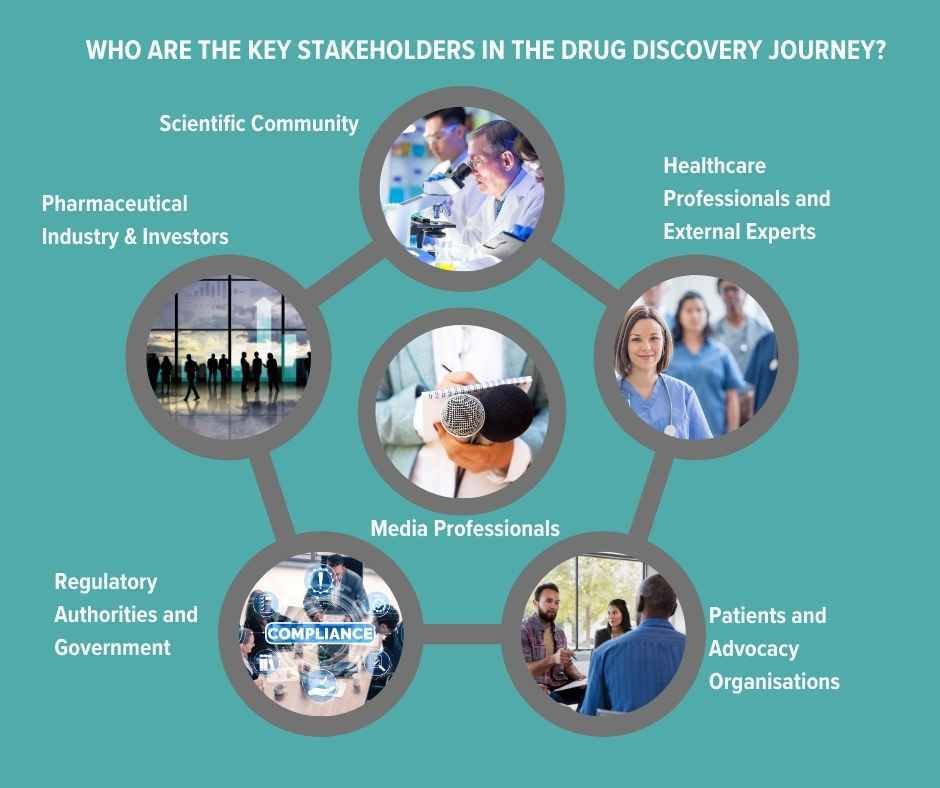

Who are the key stakeholders in the drug discovery journey?

Scientific Community: The initial stages of drug development are guided by R&D scientists and who will also be tracking others’ findings and research. Their work will also be of interest to CROs (Contract Research Organisations) who provide research services on behalf of another company, typically a pharma or biotech. They offer outsourced support such as pre-clinical research (like lab testing) to Phase I-IV clinical trials, data management, statistical analysis and regulatory submission support etc. Any communications from the pharma company about their own R&D cannot be promotional pre-launch.

Pharmaceutical Industry and Investors: These stakeholders, focused on potential profitability, play a crucial role in financing and assessing the viability of molecular candidates. Pharma companies have an obligation to disclose any information that may be price sensitive such as positive or negative results from clinical trials; granting or denial of regulatory approvals (by agencies like the FDA or EMA); product recalls or safety concerns; significant partnerships, mergers, or acquisitions; patent approvals or disputes and major changes in company leadership or strategic direction.

Regulatory Authorities and Government: Regulatory bodies and government agencies safeguard public health by establishing and enforcing the policies and regulations that oversee the development and introduction of new drugs.

Patients and Advocacy Organisations: These groups lend a voice to the needs and ethical considerations of patients, ensuring that drug development follows patient-centric and ethical principles. Engaging with them can help pharma companies support awareness campaigns, educational events, or other initiatives that benefit the patient community. But this communication must be done with a clear understanding of regulatory constraints and ethical considerations and not be promotional with a view to creating pre-launch demand.

Healthcare Professionals and External Experts: Leveraging their specialised knowledge, healthcare professionals and specialist experts (known as KOLs - key opinion leaders) provide insight and support for studies and the practical application of new medicines. Peer-reviewed publications, such as The Lancet, Nature Medicine and the BMJ, which give information on original research, clinical trials results and meta-analyses etc, still carry major authority. All data submitted by a pharma company must be accurate and not manipulated to present the drug or treatment in a misleadingly positive light. Conflicts of interest must also be declared.

Medical Media: Healthcare journalists, broadcasters and editors deepen public understanding, shaping views and perceptions of advancements in drug development. Communicating with the media before the launch of a new drug is governed by principles that make sure that information is conveyed accurately, ethically, and in compliance with regulations. It should not exaggerate the potential benefits nor downplay risks, or create an unfair demand for the drug before its availability.

ABPI Code of Practice

The ABPI (Association of the British Pharmaceutical Industry) Code of Practice provides guidelines for UK pharmaceutical companies on the promotion of medicines to health professionals and the provision of medicine information to the public. Its primary aims are:

● Accuracy: Ensuring medicine information is clear and factual.

● Trust: Upholding the industry's reputation by fostering ethical behaviour.

● Responsible Promotion: Regulating the advertising of prescription-only medicines.

● Professional Interactions: Guiding interactions with healthcare professionals.

● Transparency: Mandating the disclosure of payments to healthcare entities.

● Patient Protection: Preventing patients from receiving misleading information.

● Self-Regulation: Demonstrating the industry’s commitment to governing itself.

● Complaints Handling: Providing a mechanism to address potential breaches.

● Privacy: Safeguarding patient data and confidentiality.

Members of the ABPI are expected to follow this Code, with sanctions for non-compliance. The Code is periodically updated to stay relevant. The Prescription Medicines Code of Practice Authority (PMCPA) published Social Media Guidance for the first time in 2023, stating that pharmaceutical companies should assume that the ABPI Code would apply to all work-related, personal social media posts, for example, LinkedIn or Instagram posts/activity by their employees unless, for very clear reasons, it could be shown otherwise.

References

https://www.biopharmadive.com/news/humira-abbvie-biosimilar-competition-monopoly/620516/

Barbier, A. J., Jiang, A. Y., Zhang, P., Wooster, R., & Anderson, D. G. (2022). The clinical progress of mRNA vaccines and immunotherapies. Nature Biotechnology, 40(5), 840-854. https://www.nature.com/articles/s41587-022-01294-2

Rehman, W., Arfons, L. M., & Lazarus, H. M. (2011). The Rise, Fall and Subsequent Triumph of Thalidomide: Lessons Learned in Drug Development. Therapeutic Advances in Hematology, 2(5), 291-308. https://doi.org/10.1177/2040620711413165

https://www.abpi.org.uk/reputation/abpi-2021-code-of-practice/